“The city is a place of litter and memento. It is an archival site, where everything from bus tickets to newspapers to discarded toys is given a second chance, is replayed in a second time. Each object on the street is a tiny flash of the past and the present, both a memory and a prediction, a sign of things that have gone and things that are yet to come. It is not only the objects themselves that persist in the city, but the way they become incorporated into the language of the city: the way that street signs and building facades and graffiti speak in the voices of past generations. The city is a kind of memory machine, where even the most trivial objects are remembered and preserved, not because they have any inherent value, but because they are part of the city’s collective history. The city is a kind of trash heap, where the discarded and the forgotten are transformed into something new and valuable, where the past is constantly being repurposed and reimagined.” (Susan Stewart, On Longing, 1984.)

Mathis Pfäffli (Zürich) mainly relies on used materials and found objects, which he reassembles and alienates from their intended purpose. The suspended Collectors, made of scrap glass, inhabit the space as much as they create it. They house various found artifacts, mementos, and stories, so that the boundaries between their particular surroundings and the expansive installation, between fact and fiction, become increasingly blurred.

Using serial repetitions, Mia Sanchez (Basel) opens up distinct mental spaces: the nine photographic fragments show a walk around the playground structure Lozziwurm (1972). In her work, the artist considers the social structures and shifts between the personal and the public, as well as their political dimensions. She thereby evokes our own perception as well as our collective experiences of the urban surroundings and environment.

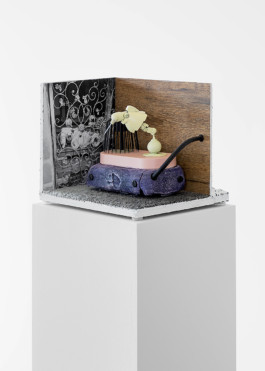

The stage-like sculptures of Erwan Sene (Paris) are distortions and mutations of various found objects. The four different models refer as much to a concrete urban landscape as to a distant dystopian world, in which the past is invaded by the present and the future. They are mise-en-scènes whose domesticity has been contaminated by the outside world, while their different forms and functions remain ambiguous yet whimsical.

“The city is a place of litter and memento. It is an archival site, where everything from bus tickets to newspapers to discarded toys is given a second chance, is replayed in a second time. Each object on the street is a tiny flash of the past and the present, both a memory and a prediction, a sign of things that have gone and things that are yet to come. It is not only the objects themselves that persist in the city, but the way they become incorporated into the language of the city: the way that street signs and building facades and graffiti speak in the voices of past generations. The city is a kind of memory machine, where even the most trivial objects are remembered and preserved, not because they have any inherent value, but because they are part of the city’s collective history. The city is a kind of trash heap, where the discarded and the forgotten are transformed into something new and valuable, where the past is constantly being repurposed and reimagined.” (Susan Stewart, On Longing, 1984.)

Mathis Pfäffli (Zürich) mainly relies on used materials and found objects, which he reassembles and alienates from their intended purpose. The suspended Collectors, made of scrap glass, inhabit the space as much as they create it. They house various found artifacts, mementos, and stories, so that the boundaries between their particular surroundings and the expansive installation, between fact and fiction, become increasingly blurred.

Using serial repetitions, Mia Sanchez (Basel) opens up distinct mental spaces: the nine photographic fragments show a walk around the playground structure Lozziwurm (1972). In her work, the artist considers the social structures and shifts between the personal and the public, as well as their political dimensions. She thereby evokes our own perception as well as our collective experiences of the urban surroundings and environment.

The stage-like sculptures of Erwan Sene (Paris) are distortions and mutations of various found objects. The four different models refer as much to a concrete urban landscape as to a distant dystopian world, in which the past is invaded by the present and the future. They are mise-en-scènes whose domesticity has been contaminated by the outside world, while their different forms and functions remain ambiguous yet whimsical.